CASE REPORT |

https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24134 |

Rhinosinus Mucormycosis with Drug-induced Pancytopenia in an Immunocompromised Severe COVID-19 Patient: A Success

1Department of Critical Care, Pushpawati Singhania Hospital and Research Institute, New Delhi, India

2Department of Internal Medicine, Pushpawati Singhania Hospital and Research Institute, New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author: Anurag Mahajan, Department of Critical Care, Pushpawati Singhania Hospital and Research Institute, New Delhi, India, Phone: +91 9810829878, e-mail: anurag06mahajan@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Mahajan A, Tandon VS. Rhinosinus Mucormycosis with Drug-induced Pancytopenia in an Immunocompromised Severe COVID-19 Patient: A Success. Indian J Crit Care Med 2022;26(3):395–398.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Secondary infections in coronavirus disease (COVID) are becoming common. We report a case of a female known case of diabetes, sarcoidosis on steroids and methotrexate admitted with COVID pneumonia. She was treated with steroids, remdesivir, and anticoagulants and was discharged. She revisited the hospital after 2 months with complaints of severe right-sided headache, eye pain, and vomiting. Magentic resonance image of brain and paranasal sinus revealed possibility of invasive rhinosinus mucormycosis. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) was done and culture showed growth of mucor and methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) following which she was started on amphotericin B and antibiotics. She also developed methotrexate and amphotericin B-induced pancytopenia for which injection folinic acid, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and erythropoietin were given and was switched over to liposomal amphotericin B. After 5 days of ventilatory support, she was discharged in a stable condition. Extensive steroids in an immunocompromised patient might have led to this event hence physicians should always keep this possibility of secondary fungal infection in COVID patients for understanding the impact of disease.

Keywords: COVID pneumonia, Diabetes, Immunocompromised, Pancytopenia, Rhinosinus mucormycosis.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus pneumonia has been presenting with variety of symptoms which include fever, cough, dyspnea, loss of smell, and constitutional symptoms. Patients with known diabetes, CAD, CVA, and elderly are more predisposed to this illness. Apart from these symptoms, a variety of fungal infections can also be seen especially in the population who are immunocompromised and are on long-term steroids. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is one such entity. We encountered a case of rhinosinus mucormycosis in an immunocompromised elderly woman where prompt diagnosis and early management helped us save her life.

CASE DESCRIPTION

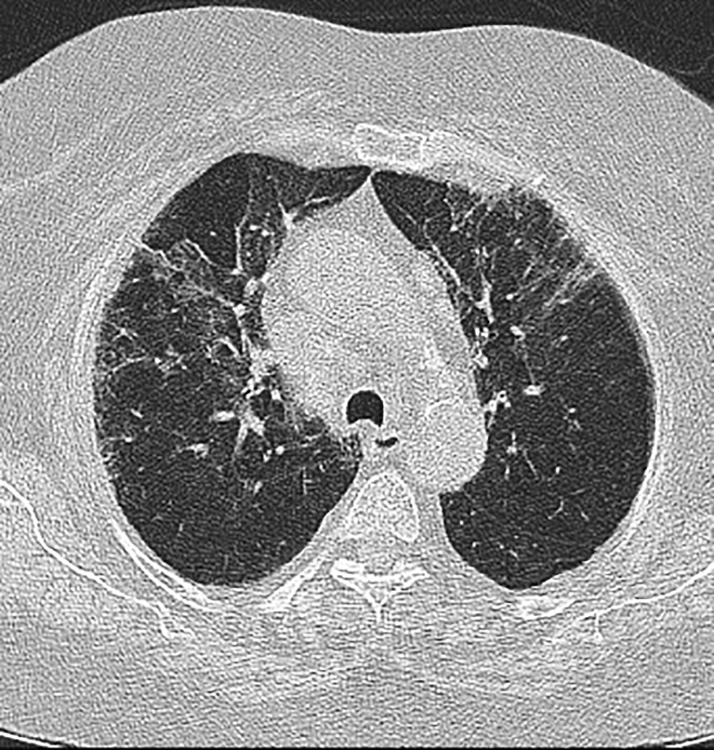

A 70-year-old woman presented with history of fever, breathing discomfort, and cough since 3 days. She was a known diabetic on oral hypoglycemic agents (OHA), interstitial lung disease (ILD) on methotrexate 15 mg weekly, and low dose steroids, old left-sided hemiparesis on tab ecosprin 75 mg od. On examination, she had pulse rate of 110/min, SpO2 of 86% on room air, BP 140/90 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed bilateral chest crepts. Her RT-PCR for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was done which was positive. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest (Fig. 1) revealed bilateral ground glass opacities with severity score of 16 thereafter she was treated with injection remedesivir for 5 days, methylprednisolone IV in a dose of 40 mg thrice a day with injection clexane 0.6 mL sc twice daily. In view of persistent dyspnea, she was shifted to the medical ICU wherein she was given BiPAP support along with two units of plasma therapy. The same line of management was continued and gradually she was weaned off the BiPAP support and was discharged in stable condition on steroids, OHA, and other medications.

Fig. 1: HRCT showing ground glass opacities

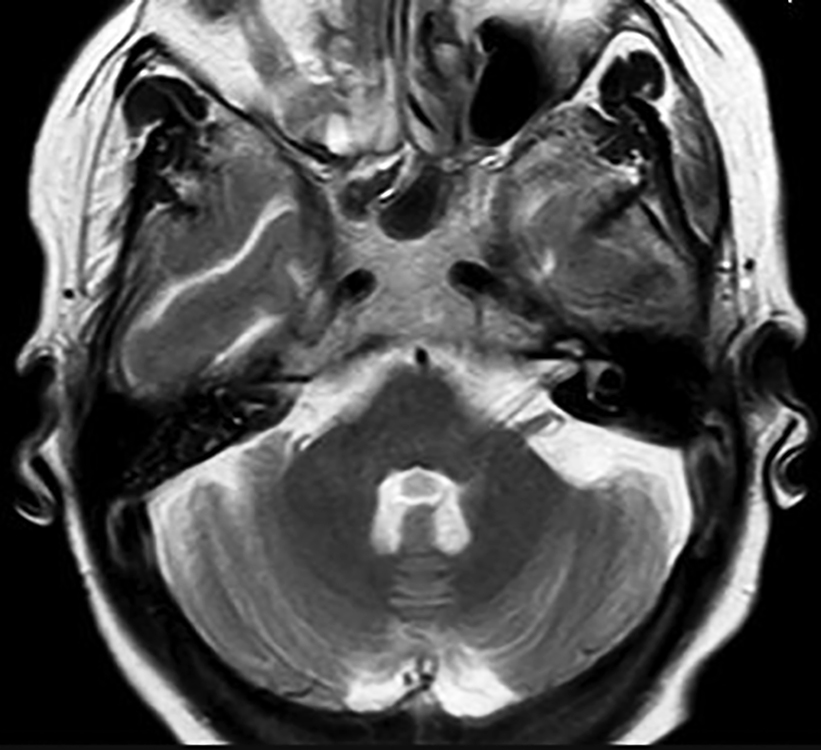

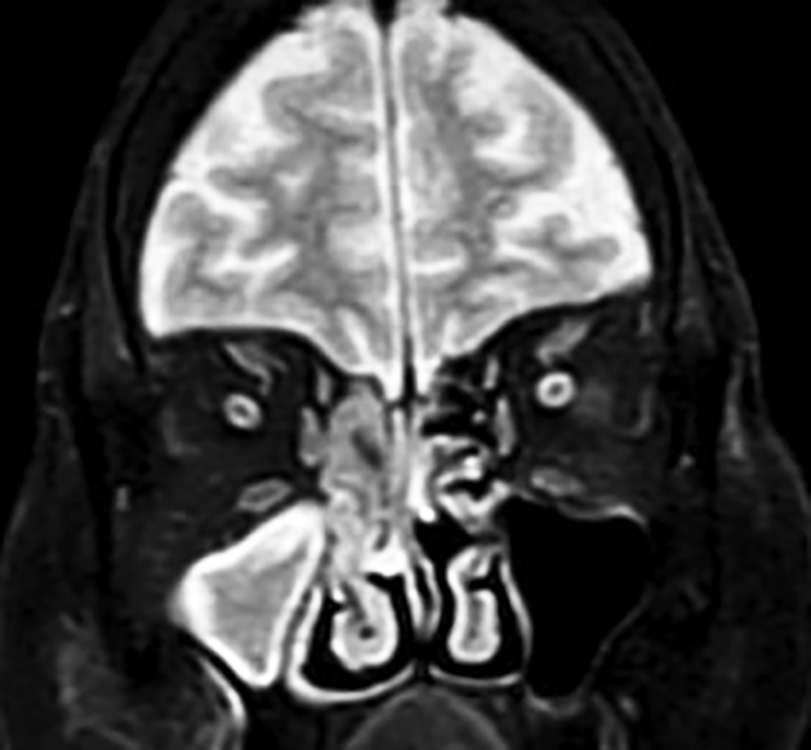

After 2 months, she again presented with the history of right-sided headache, eye pain, and vomiting. On examination, she had tachycardia and SpO2 of 88% on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with redness over right eye and facial edema. Blood investigations were done, hemogram revealed Hb 11g%, total leukocyte count (TLC) 24,000, platelet 232 lakhs, and creatinine 2.92. In view of headache, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain was done, which revealed microvascular changes. Keeping a possibility of fungal sinusitis, HRCT paranasal sinuses (PNS) (Figs 2 and 3) was done, which showed sinonasal inflammatory process following which urgent MRI paranasal sinus and orbit (Figs 4 to 6) was performed, which showed suspicion of invasive fungorhinosinusitis, orbital cellulitis, and optic neuritis.

Fig. 2: HRCT PNS showing sinonasal inflammatory process

Fig. 3: HRCT showing sinonasal inflammation

Fig. 4: MRI PNS showing possibility? Rhinosinus mucormycosis

Fig. 5: MRI PNS showing possibility? Fungal rhinosinusitis

Fig. 6: MRI PNS showing possibility? Fungal rhinosinusitis

Ophthalmology consultation was taken, which confirmed presence of orbital cellulitis with impending optic neuritis. Nasal swab was taken, which came out to be negative for fungus. ENT consultation was taken and FESS was done. Pus was sent for culture, which revealed growth of mucor with Staphylococcus aureus. The patient was intubated during FESS and was started on amphotericin B (lipid formulation) 250 mg once daily with sensitive IV antibiotics for MRSA. After five days of therapy, her blood investigations revealed Hb 9.7g%, TLC 2.91, and platelet 115 lakhs with normalization of kidney function tests.

On day 10th of hospital stay, Hb was 8.7g%, TLC 1.24, and platelet 53,000. Peripheral smear showed pancytopenia with lymphocytosis. Iron profile revealed low iron 24, low total iron binding capacity (TIBC). Vitamin B12 and folate were normal. To rule out possibility of hemolysis post COVID, DCT and ICT were done, which were negative. She also started having nasal bleed and the possibility of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) was ruled out with D-dimer 927, normal fibrin degradation products (FDP) and International normalized ratio (INR). She was given fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelets in view of ongoing epistaxis. The pancytopenia was attributed to the ongoing drug methotrexate, which was stopped and IV folinic acid was initiated. Despite stopping the drug, the patient continued to have pancytopenia for which amphotericin B was found to be the possible causative factor. She was treated with G-CSF injections with erythropoietin and she was switched on to liposomal ampho-B. Her repeat hemogram done on the 15th day revealed Hb 12.1 g%, TLC 5.41, and platelet 112,000. After 5 days of ventilatory support and 14 days of IV amphotericin B in hospital, she was discharged on IV ambisome, OHA, and other antibiotics and was shifted to oral posaconazole as a step down therapy during follow up. Since then she is asymptomatic and is currently doing well on her medications.

DISCUSSION

Mucorales are known to cause mucormycosis. It can be classified as cutaneous, pulmonary, rhinocerbral, renal, and gastrointestinal. Multiple factors such as preexisting lung pathology, diabetes mellitus, long-term steroids, use of any immunosuppressants and antibiotics, prolonged neutropenia, and hematological malignancies may lead to any secondary infections specially fungal.1

An Indian report of 465 patients showed that rhino-orbital mucormycosis was the most common (67.7%) presentation followed by pulmonary (13.3%), cutaneous (10.5%) with diabetes mellitus (DM) being the most common factor around 73.5% followed by malignancy (9.0%) and transplant (7.7%).2

Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is the most common type found in diabetics.3 A review of 179 cases of rhino-orbital mucormycosis concluded that 70% of all patients had DM and the presenting features were pain over the face, orbital area, headache, nasal congestion, proptosis, blurred vision, and signs of orbital cellulitis.4 The fungus enters the paranasal sinuses through inhalation reaching up to the cavernous sinus and causes the formation of palatal and nasal necrotic eschars, destruction of the turbinates.5

A review of 208 cases of rhino-orbital mucormycosis published showed the frequency of symptoms as fever (44%), nasal ulceration (38%), periorbital swelling (34%), decreased vision (30%), ophthalmoplegia (29%), sinusitis (26%), and headache (25%).6

Werthman–Ehrenreich reported a case of mucor in a diabetic COVID patient with left-sided ptosis and proptosis with altered sensorium.7 Brain imaging is essential wherein CT is more sensitive than MRI to detect bony erosions, while MRI specifies the extent of involvement of brain, orbit, and sinuses.8

Apart from the routine cultural techniques, PCR with sequencing can be used. Endoscopic evaluation of sinuses should be performed for tissue necrosis.9

Early initiation of the therapy ameliorates the outcome. The treatment of choice remains amphotericin B with monitoring of the renal functions. Lipid formulation of amphtericin B can be preferred over amphotericin B deoxycholate to deliver high dose with less nephrotoxicity. For patients who have responded to amphotericin B, posaconazole, or isavuconazole can be used as a step down therapy after continuing amphotericin B until the patient has shown signs of improvement or in patients who do not respond or are intolerant to amphotericin B.10 In a salvage study, the clinical efficacy of posaconazole revealed that it resulted in complete or partial response in 60% of patients, 21% had stable disease. Creatinine should be regularly monitored and if it starts rising, tablet formulation of posaconazole extended release or switch to IV isavuconazole should be considered.11 Treatment extends for years and sometimes lifetime if immunosuppression cannot be corrected.

A review of 208 patients concluded that the most significant factors that contributed to mortality were delayed diagnosis, bilateral sinus involvement, renal disease, and use of deferoxamine. Mortality ranges from 25 to 62%. Prognosis is best in patients with infection confined to the sinuses and is poor in patients with brain involvement, involvement of cavernous sinus or carotid artery.12,13

CONCLUSION

There can be many secondary bacterial and fungal infections associated with COVID-19. The widespread use of steroids, broadspectrum antibiotics play a crucial role. Physicians should be well acquainted with the possibilities of existence of underlying fungal infection in patients with preexisting comorbidities like diabetes, malignancies, post transplant patients, and patients who are on steroid therapy, immunomodulators and COVID-19 disease.

In our patient, long-standing diabetes, imunocompromised state due to ongoing methotrexate, lymphopenia, and steroids predisposed the patient to mucor infection and timely intervention saved her life. Thus early clinical suspicion of the disease and timely management will result in the reduction of morbidity and mortality and can be lifesaving.

ORCID

Anurag Mahajan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5678-6055

Vineeta Singh Tandon https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6788-8612

REFERENCES

1. Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, Ranganathan N, Skolimowska K, Gilchrist M, et al. Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals With Coronavirus: A Rapid Review To Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71(9):2459–2468. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa530.

2. Patel A, Kaur H, Xess I, Michael JS, Savio J, Rudramurthy S, et al. A Multicentre Observational Study on the Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Management and Outcomes of Mucormycosis in India. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26(7):944.e9–944.e15. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.11.021. Epub 2019 Dec 4.

3. Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Poirée S, Kania R, Lortholary O. Diabetes and Mucormycosis: A Complex Interplay. Diabetes Metab 2012;38(3):193–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.01.00. Epub 2012 Mar 3.

4. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis: Predisposing Factors. Laryngoscope 1982;92(10 Pt 1):1140–1143. PMID: 7132514.

5. Riley TT, Muzny CA, Swiatlo E, Legendre DP. Breaking the Mold: A Review of Mucormycosis and Current Pharmacological Treatment Options. Ann Pharmacother 2016;50(9):747–757. DOI: 10.1177/1060028016655425. Epub 2016 Jun 15.

6. Yohai RA, Bullock JD, Aziz AA, Markert RJ. Survival Factors in Rhino-Orbital-Cerebral Mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1994;39(1):3–22. DOI: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80041-4.

7. Werthman-Ehrenreich A. Mucormycosis with Orbital Compartment Syndrome in a Patient with COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 16]. Am J Emerg Med 2020;S0735–6757(20)30826–3. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.032.

8. Aribandi M, McCoy VA, Bazan C 3rd. Imaging Features of Invasive and Noninvasive Fungal Sinusitis: A Review. Radiographics 2007;27:1283. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.275065189.

9. Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic Diagnosis of Fungal Infections in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24(2):247–280. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00053-10.

10. Andes DR, Ghannoum MA, Mukherjee PK, et al. Outcomes by MIC Values for Patients Treated with Isavuconazole or Voriconazole for Invasive Aspergillosis in the Phase 3 SECURE and VITAL Trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;63(1):e01634–18. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01634-18.

11. Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, Mullane KM, Perfect JR, Thompson GR 3rd, et al. VITAL and FungiScope Mucormycosis Investigators. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(7):828–837. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00071-2.

12. Weprin BE, Hall WA, Goodman J, Adams GL. Long-term Survival in Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis. Case Report. J Neurosurg 1998;88(3):570–575. DOI: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0570.

13. Shah PD, Peters KR, Reuman PD. Recovery from Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis with Carotid Artery Occlusion: A Pediatric Case and Review of the Literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16(1):68–71. DOI: 10.1097/00006454-199701000-00015.

________________________

© The Author(s). 2022 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.